From the moment we arrive on this earth, somewhere, an unseen timer is turned, and with each drop of sand that falls, counts down to the time when our sand will run out, our life will run its course and we will breathe our last.

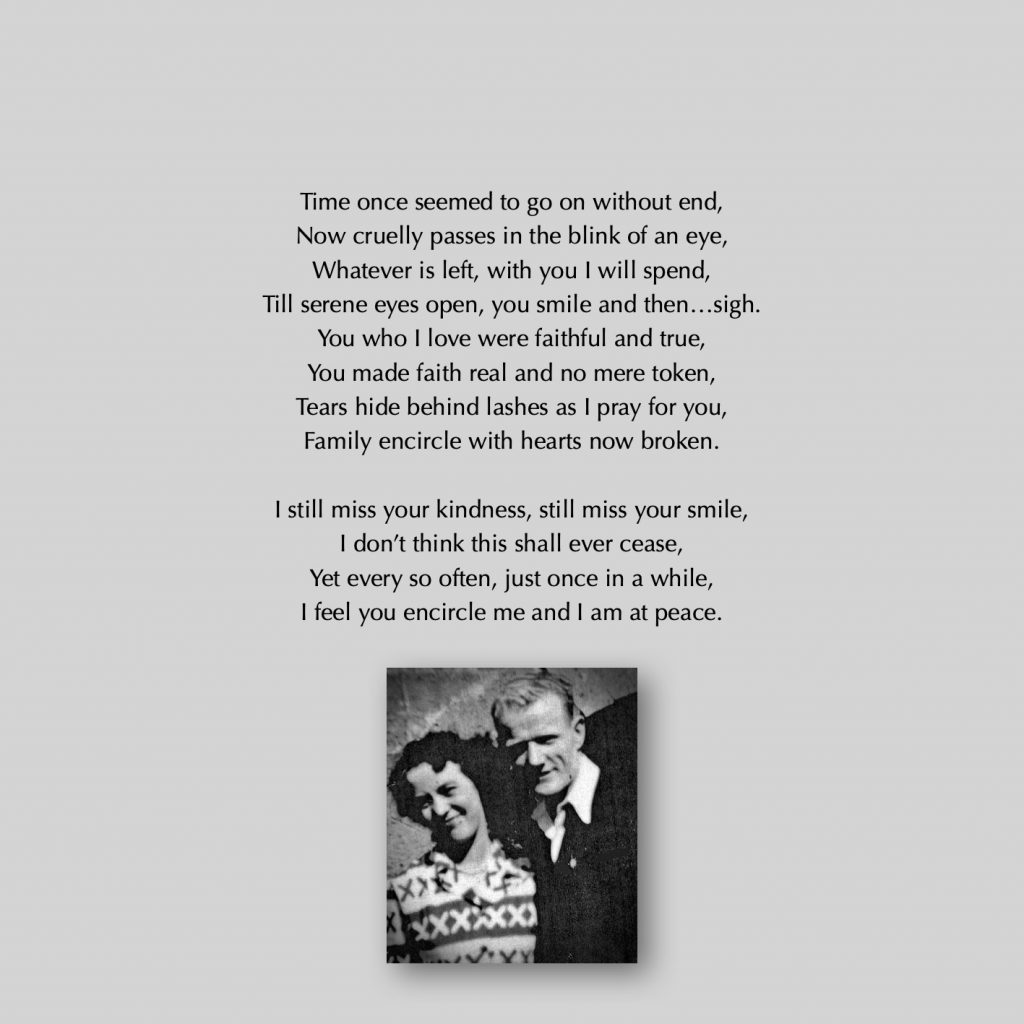

My first substantive experience of a Death took place some seventeen years ago. My paternal grandmother had suffered a serious and debilitating stroke.

Upon hearing this news, a series of wheels were set in motion. Family members were called. Troops were rallied. An armada of O’Reilly’s and Cregan’s (my grandmother’s maiden name) descended upon the Tower Block of the City Hospital in Belfast and commenced a night vigil.

Cousins who had not seen each other for some time, and others who saw each other regularly, huddled on a cold linoleum floor sharing stories and filling up on bleak and bland scalding drinks from a vending machine. An ailing matriarch’s children engaged in conversation, discussing that which nothing in life can prepare us for; the loss of a parent. Aged brothers and sisters shared rows of screwed down plastic seats, turning their hats in their hands and saying little.

Life can have its own way of shocking us into action. On that initial evening we expected my grandmother to pass away. As life has its own way of surprising us, so did she. The stroke was debilitating to be sure, but she wasn’t giving in just yet. And so over the next months a steady vigil continued unabated.

When my grandmother was moved into a private room, we followed. We occupied the space with her. Family members would stay overnight with her, keeping a careful watch for any change. In the mornings her brothers and sister would take up the watch. In the evenings, family time was spent encircling her, sharing stories about her and telling jokes. We began to bring flasks of tea and coffee and food into the room.

On one occasion I recall someone even had a cheese board, grapes and crackers which balanced precariously on the hospital bed. As we as a family grew closer together, life ebbed away from my grandmother, breath by ever shortening breath. Every so often I found my attention diverted from the strengthening family ties to look at her. There were times when she smiled underneath her oxygen mask. No illness could take this away from her and no human frailty could break her spirit. There were even times she would open her eyes and look round; her life’s work now complete.

I believe my grandmother was in a way preparing us for her eventual death. Perhaps she needed to know that we would be ok. Perhaps she just wanted to spend one more day with her family together; as it happened she had almost five months of constant fellowship. A life well lived indeed.

In the days of her wake those ties of family and fellowship continued, albeit with something missing. Her. Family flew in from America, and visitors from all over Ireland and beyond descended upon her house. We began to take a tally of the number of priests and nuns who would visit. The local fish and chip shop did a roaring trade for those few days, with steaming paper bags on trays, smelling of fish and vinegar that stacked on top of each other. Paper plates and plastic cups were all we needed, and a knee to balance them on.

In all that time, I didn’t once cry. Not once. Plenty of other family members did, and her children each had their moment where they broke, but not me. Even watching my Grandpa now lost in his own dementia standing over her coffin, the grief awakening something that was perhaps forgotten in him did not make me cry.

The morning of her funeral came around. I found myself decked out in a suit that was of course altogether too big for my narrow frame (“You’ll grow into it.”) and back in the family home. Again, the transition from preparing for her death, to waking her, to now preparing to say a final goodbye was so strange. The mood was sombre. Mourners arrived in their best black clothing. Family did not say much.

As the priest arrived to begin the final prayers before leaving the home I was sat on the stairs with my cousins. We began the praying of the rosary. I have always been a person of faith, but it didn’t have much impact on me that day. It just felt like words, with little meaning. We carried my grandmother to the church on our shoulders. My brother, four of my cousins and I completed the final ‘lift’ before she would be brought into the church. Memories of time spent with her since childhood flew through my mind, and the sound of her wicked laugh. We’d never been as close as I was with my maternal grandmother but still, she was my granny. I loved her. And she was gone. As I prepared to release the coffin to handover to my dad and those that would do the last lift, something in me broke.

Pain. Awful pain. Grief washed over me like a tidal wave and in some ways, I felt as though I was suddenly drowning in it. Tears were all I could see, and loss was all I knew. It was not like anything I had experienced before. The finality of this moment encompassed me, and I broke. My brother put an arm around me. I reached up and held his hand, and we walked together to say our last goodbye. The rest of the day is a blur to me, but not the people. I remember exactly those that shared my grief on that day. I can still see them vividly in my mind’s eye.

In the sharing of this grief, that collective mourning, the at times wail of lament, we are given the opportunity to bare our very humanity with those around us. We allow others the opportunity to see us at our most vulnerable, and in so doing we place our trust in them, to not abuse that humanity. It was a remarkable, transformative experience. It changed me permanently. For the better. For one thing, ever since that day, I am now very free with my emotions and I am eternally grateful for this.

As our time on the Fellowship programme has gone on and now nears its conclusion, we engaged in a conversation tonight with the Irish creator (the only word I can think of!) Pádraig Ó Tuama and author and kindred spirit Elif Shafak. We discussed these matters such as life and grief that cannot be quantified, but can only be shared. I relay the story above because, through this incredible conversation tonight, I have learned the power of a shared grief.

Within the context of the north, we have become so wrapped up in our past, and who’s to blame for this or that and who did what to who and where that we have not allowed ourselves the space or freedom to grieve as a collective society. And a shared grief is something which we need. We have reached a stage where we even politicise grief. We shout at the top of our lungs about Legacy but do nothing to embrace our shared Humanity.

I surely owe it to my grandparents to give thanks for the life they prepared for me and live it. I do not believe I would honour them by yearning for simpler times of the past, thinking isn’t life oh so cruel for taking them away from me and not live.

What would our politics look like if we actually embraced that? Would we be so eager to point fingers and play who’s to blame? Would we allow the current attitude of brinkmanship to smother us? Do we commemorate our glorious dead by remaining so stuck in their past, that we do not honour them by cherishing the present that they gave us and build for a future which we ourselves will not see?

It may be crude to draw a comparison, but it reminds me of that day of the funeral when I could not cry. When will come our breaking point? When will we allow ourselves to be vulnerable; to share our pain, our tears and our grief? How often scenes of a political funeral are shared around the world; funerals that force the hand of friendship and shared grief. Why should it be that we can only share our humanity at a funeral? Let’s share it together everyday.

It’s a question each of us have to answer. As I have spent the last number of months in the CDPB Fellowship Programme I have felt bonds of friendship, love and fellowship form and strengthen. It is a period of preparation. As we near our conclusion I feel those familiar twinges of expectant grief in my heart. I know what’s coming; we will soon experience our own Breaking of the Fellowship, and I must make the necessary preparations for this within and outside myself.

However, the bonds of fellowship that have grown over these months will not break. We are stronger, and stronger together. As the programme nears its conclusion, I embrace this with hope; at peace in the knowledge that within this fellowship I am safe. For me, that is a Legacy of shared Humanity which can only be a good thing. After all, none of us can ever know how many grains of sand we have left. Use them wisely.

Dominic O’Reilly